Traveling the vast distances between solar systems is far beyond the limits of current technology. But a new ultra-thin light sail designed with AI could make it possible to reach the nearest star within 20 years.

Voyager 1, launched in 1977, was the first man-made object to leave our solar system. But at current speeds, it would take over 70,000 years to reach Alpha Centauri, the nearest star system to our own.

However, there is one propulsion technology that could speed things up significantly. The light sail is a large reflective surface located in front of the spacecraft where it can use either sunlight or light from a terrestrial laser to continuously accelerate the vehicle. In theory, this could make it possible to reach speeds of 10 to 20 percent of the speed of light.

Building materials that are both reflective and light enough to make this possible, however, presented a unique challenge. Now, researchers have used an AI technique called “neural topology optimization” to create a nanometer layer of silicon nitride that could bring this idea to life.

“This mission requires materials for light sails that challenge the foundations of nanotechnology and require innovations in optics, materials science, and structural engineering,” the team writes in a preprint published on arXiv.

“This study underscores the potential of neural topology optimization to achieve innovative and economically viable light sail designs that are key to next-generation space exploration.”

The researchers’ technique was inspired by Breakthrough Starshot, a project launched by Breakthrough Initiatives in 2016. Starshot seeks to design a fleet of about 1,000 small spacecraft that use light sails and a terrestrial laser to reach Alpha Centauri within 20 to 30 years. The probes would carry cameras and other sensors that would send back data upon arrival.

To reach the required speed, the spacecraft will have to be incredibly light – the probes themselves will be only centimeters in diameter and weigh a few grams. However, to get enough light, the sails need to be roughly 100 square feet, so we need new ultra-lightweight materials to support their weight.

One promising approach involves the creation of optical nanostructures called “photonic crystals,” which consist of a repeating grid of tiny holes. Punching millions or trillions of these holes into a material greatly reduces its weight, but these repeating structures also create unusual optical effects that can actually increase the material’s reflectivity.

Figuring out exactly how to arrange these holes is a complicated process, however, so a group from Delft University in the Netherlands and Brown University in the United States enlisted the help of AI. They combined a neural network with a more conventional computational physics program to find the most optimal configuration and shape of the holes to minimize weight and increase reflectivity.

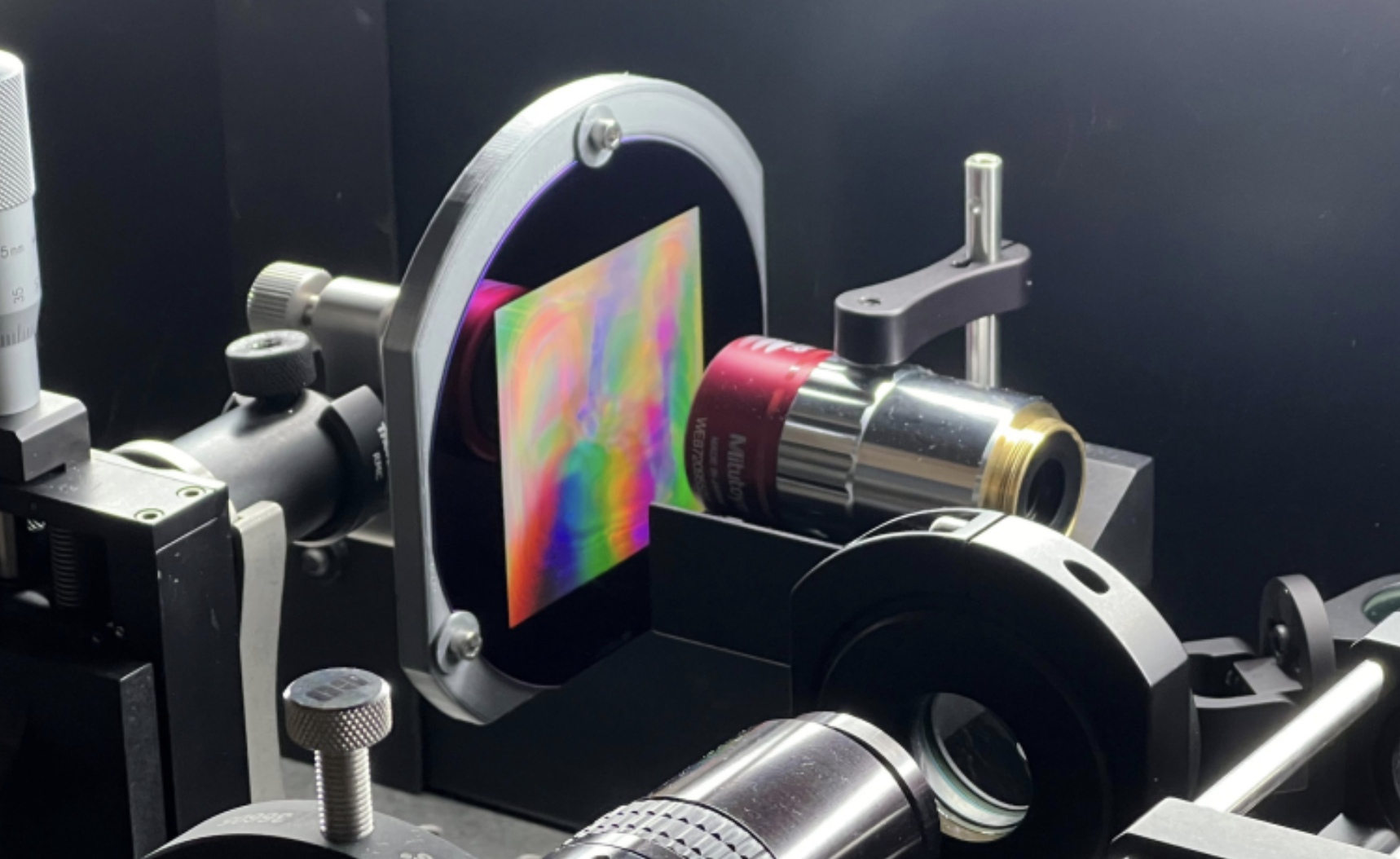

This resulted in a grid of bean-shaped holes less than 200 nanometers thick. To show that the design works as expected, they used an approach called flood lithography, in which a laser uses an incredibly detailed template to create holes in a wafer of silicon nitride. Using this approach, the team created a 5.5-square-inch sample that weighed just a few micrograms.

Lithography is the same technology companies use to make computer chips, so the researchers think the approach could easily be scaled up. The team predicted that the full-size sail would take about a day to create and cost around $2,700. But they would need to build a dedicated facility, said team leader Richard Norte of Delft The new scientistbecause those used for chip manufacturing only work with wafers about 15 inches long.

Many other technical issues still need to be resolved for the Breakthrough Starshot mission to come together, said Stefania Soldini of the University of Liverpool. new scientist but the decisive factor will be the cheap and fast way of producing light sails.

NASA is also actively monitoring the approach. Just last week, the agency announced that its Advanced Composite Solar Sail System, which launched earlier this year, is closed for sail raising for the first time.

If these projects are successful, we may get our first close-up look at worlds outside our solar system in many people’s lifetimes.

Image credit: This 4.5-inch sample could lead to a full-scale light sail light enough to tow a small spacecraft to another star system / L. Norder, et al via arXiv